As we have been nearing the end of 2016, and knowing that I’d like to start creating a small amount of (local) buzz about my game, I thought it was a good time to consider doing some promotional work so that people can look forward to its (eventual) release. Since this project is very much rooted in my research as an academic artist and designer, I thought it would be best to work from within on the initial information release. Working with Jerry Poling, the Assistant Director of University of Wisconsin-Stout’s Communications, we crafted a press release that would be directed at local media outlets. Jerry’s UW-Stout release write-up was fantastic, capturing the research aspect of the game in a way that I could have never done.

That release ended up catching the attention of a few different outlets. I thought I’d take this post to do a round-up of those, so as to create a one-stop archive post of Fall 2015 press for Tombeaux.

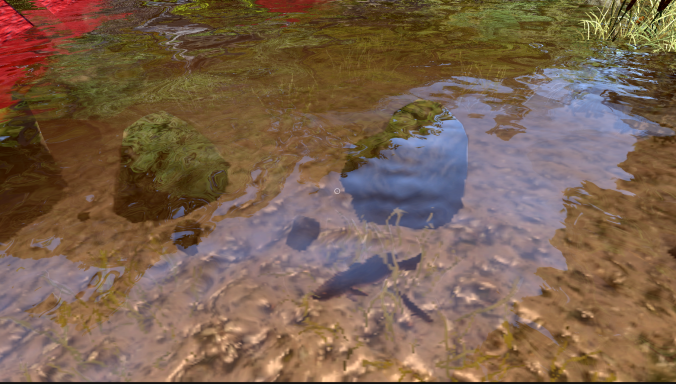

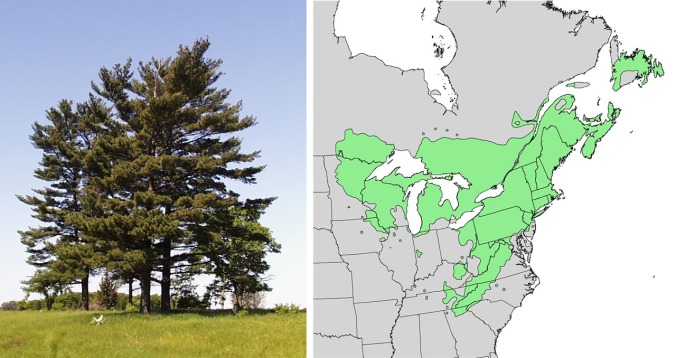

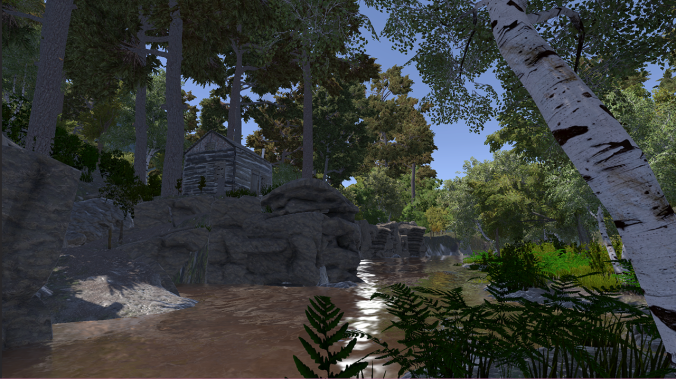

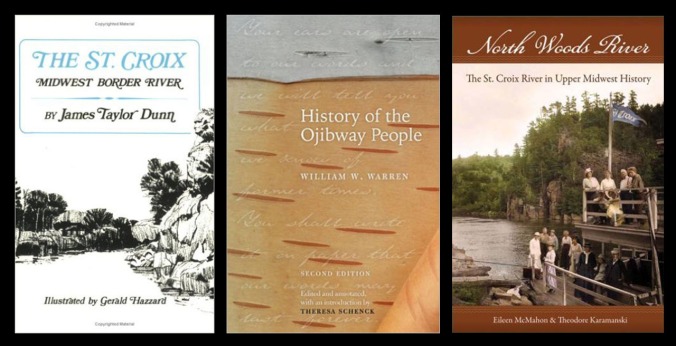

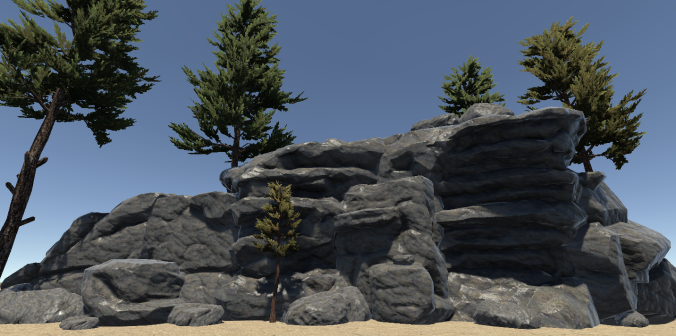

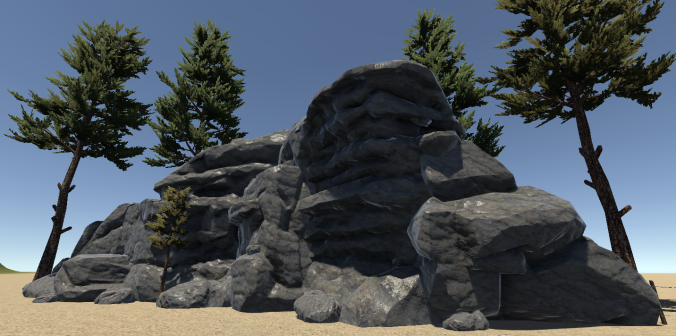

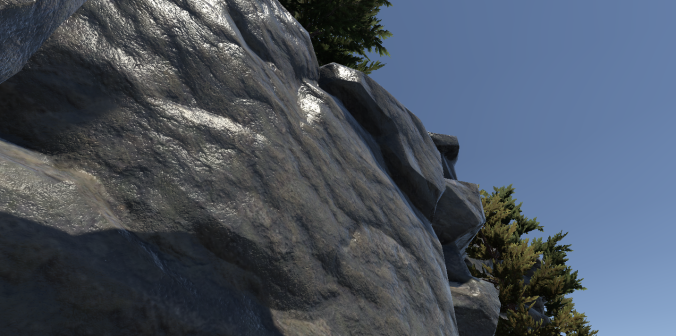

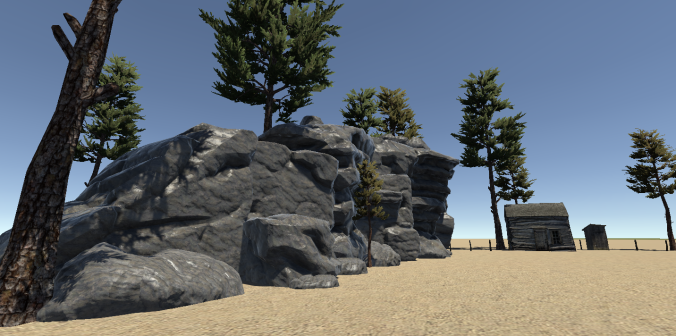

St. Paul’s daily newspaper, the Pioneer Press, ran a nice piece about Tombeaux on their November 9th Monday edition. I was quite surprised to find it on the front page, as once I saw that I really wished some of the visuals from the game could have been represented there as well (but who am I to complain about front page press?!?). Their online version of the article did the game more visual justice, through a handful of in-game screenshots. Furthering the life of that article, the Duluth News Tribune re-ran the piece, which might have had more of an appeal in thre great northern, wilderness-focused mini-metropolis. Kelsy Ketchum, the reporter for the story, also interviewed Jennifer Sly of the Minnesota Historical Society about the piece:

“One challenge in video games set within a historical period is that you want to give players agency and choice, but it’s hard to do that without changing the historical timeline… Dave Beck’s work is one way to let users explore history in different times.” – Jennifer Sly, Minnesota Historical Society

Following fast on the heels of the Pioneer Press article, I was contacted by Wisconsin Public Radio’s Central Time hosts to do a short on-air interview. I was expecting to either receive prompts or questions ahead of time, but being a daily news show, they cut straight to the chase in a live, rapid-fire-question format. They actually cut me off halfway through my final answer/statement, but it was still great experience. You can listen to the full WPR piece here, or below.

WPR’s Central Time Interview from 11/19/15

Ironically, the initial stage of PR reached further than my local hometown area, crossing in to Minnesota and reaching to the far eastern edge of Wisconsin. After a few weeks of being featured around the region, it finally came home to roost, with a really nice feature online and in print by Nikki Lanzer in Volume One. Volume One is a bi-weekly arts and culture paper out of Eau Claire, WI. Her article was short and to the point, complete with a catchy (albeit cheesy) title of: “Tombeaux-lievable”

“Beck expects Tombeaux to engage players in a completely new way than what they’ve grown accustomed to from other computer games, giving them a refreshing and unique experience that will foster both historical awareness and appreciation for the St. Croix and its surroundings.” – Nikki Lanzer, Volume One

So, with the help of my university’s communications department (and a little overtime on PR myself), I’m happy with how Tombeaux has done in the public sphere up to now. This is especially so, given that there is so much left to do in the game for it to be called finished! Here’s hoping that 2016 shows as much success and attention as in this previous year.

See you in 2016!